Our Subject

CLICK IMAGE BELOW TO WATCH THE VIDEO

A Level Sociology FAQs

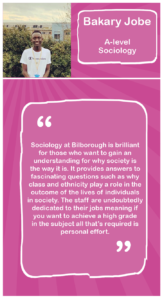

How can we explain the role of gender difference in life chances? Why does poverty exist – and persist – in contemporary society? What are the problems with defining and measuring social class? Sociology is the study of society – the social world in which we live. As individuals, we are shaped by our family, our friends, the education system and the media. Sociology explores the ways in which society influences us – and the way that we in turn influence wider society.

To study Sociology at Bilborough, you need a minimum grade 4 in Maths and grade 5 in GCSE English Language, as there is an expectation of writing complex extended essays. You must also have a strong interest in current affairs.

Our links with HE

Many Sociology graduates are attracted to careers that centre on the challenges and demands faced by members of society. This leads to jobs in social services, education, criminal justice, welfare services, government, counselling, charities and the voluntary sector. So you could find yourself working as a charity fundraiser, community development worker, counsellor, lecturer, housing officer, teacher, probation officer, social researcher, social worker or welfare rights adviser … to name but a few career options!